Murder on the Llangollen Canal

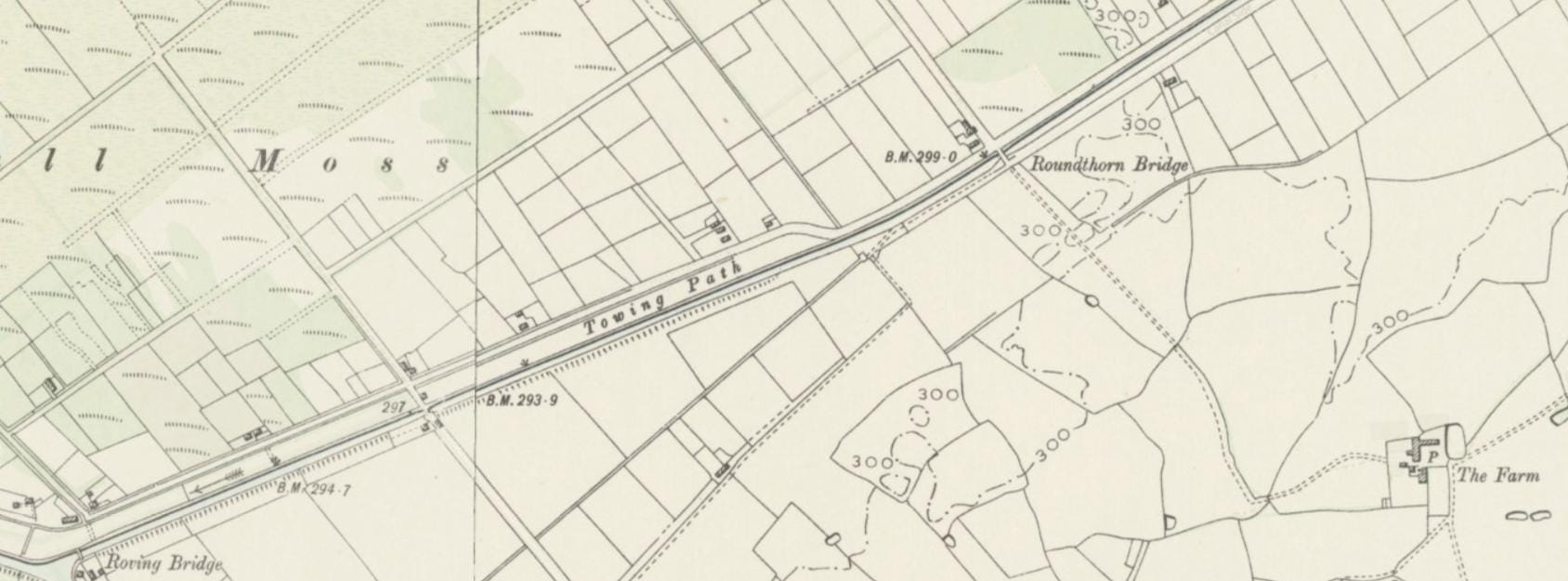

This story of Thomas Newbrook of Whixall, his employer Elijah Bowers Forester, and Elijah's brother-in-law, William Powell, takes place at Round Thorn Bridge on the Llangollen Canal.

This story of Thomas Newbrook of Whixall, his employer Elijah Bowers Forester, and Elijah's brother-in-law, William Powell, takes place at Round Thorn Bridge on the Llangollen Canal.

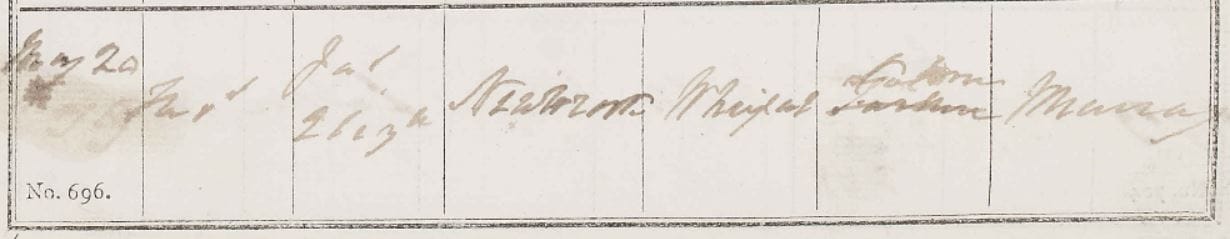

Thomas Newbrook was born in Whixall in 1838, the son of James Newbrook, an agricultural labourer, and Elizabeth nee Davenport.

He joined the Royal Welch Fusiliers 23rd Foot (Private 1413) on 8th December 1865. He was 24 years old, 5 feet 6 inches tall, with a sallow complexion, brown hair, and hazel eyes. He had a scar from a bubo on his left groin and another scar from a boil on the right side of his neck. He served for one year and 294 days in Bombay, India, where the Royal Welch Fusiliers had remained after the Indian Mutiny. The Royal Welch Fusiliers remained in India until 1869 when they returned to Britain.

Thomas’s military behaviour in India was sometimes good, and he was in possession of one good conduct badge. However, his name was three times in the regimental defaulters book, although he was never court martialled. In 1866 he was imprisoned for seven days for using improper language.

Thomas was approved for discharge from the Regiment on 7th September 1868 as he was suffering from Hepatitis Chimera. He was finally released at Netley on December 22nd 1868. On discharge he was delicate and unable to help himself. He was told that if he recovered he would not re-pass for service due to leech bites and blister marks, however it was believed that his health would improve and he might in time be able to contribute to his own livelihood. He was granted a pension.

Things did not go well for Thomas. Soon after his return to Shropshire, between April and 1870, his mother died. Soon after this, on 26th May 1870 he was charged with drunken and riotous behaviour, and was given 14 days’ hard labour. He was then sentenced twice for stealing, firstly for taking two cucumbers, and secondly, on 28th October 1871, for stealing bread when he was hungry. As a result of being detained in prison in 1870 his army pension was suspended for three months. In 1874 he was sentenced to 6 months’ imprisonment and 2 years’ police supervision for larceny after two previous counts of felony. He was remanded again for stealing onions and cauliflower from the garden of the Pheasant Inn in Whixall, at ten to midnight on the 11th May 1875 and was given seven days’ hard labour. On the 25th of April 1877 he stole twelve fowl, the property of Margaret Hales, in Whixall, and was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude. In 1881 he appears in the census at Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight.

About six to eight months after his release, Thomas attempted to commit suicide by drowning himself in the canal near Platt Lane. In those days committing suicide was a criminal offence. On Monday 11th June 1883 he was brought up in custody at Whitchurch Police Court, before T H Sandford and R P Ethelston, Esquires, charged with attempted suicide. Benjamin Egerton, a shopkeeper in Whixall, appeared as a witness. He stated that on June 10th 1883 at about 9.30pm he was on the way home when Thomas passed him, walking from the Waggoners’ Inn at Platt Lane to the canal. (The Waggoners’ Inn was destroyed by fire in 2008 and has since been demolished). Thomas said to Benjamin, “Watch me drown myself,” and immediately threw himself into the canal and resurfaced on the other side. A man named Heath was passing, and with some difficulty managed to pull Thomas out of the canal, although he was not too keen to be rescued, shouting “Loose me, I intend to drown myself!” The witnesses informed the local policeman, PC Wildsmith, who lived nearby, and Thomas was taken to Whitchurch police station. There, Superintendent Howells remanded him in custody at Shrewsbury Gaol to await the Petty Sessions on the following Friday. At the Sessions Thomas admitted the charges, and said that he had been drinking, only a small quantity, but alcohol affected him more since he had had sunstroke in India. He did not know what he was doing at the time. He was discharged with a caution.

In January 1885 Thomas was fined ten shillings for drunkenness, then in June 1885 he was fined five shillings, again for drunkenness.

By September 1887 Thomas was working as an agricultural labourer for Elijah Bowers Forester, who was the tenant of a farm in Whixall. Elijah was about 30 years old. Thomas had known Elijah since he was a baby, and thought of him as a quiet man, who was kind to his wife and family. Elijah’s brother in law (his wife’s brother), William Powell, moved into a neighbouring farm, Round Thorn Farm, also known as Manor Farm, in May 1886.

Up until now, perhaps you thought Thomas would be the murderer in this story, but this is where things take a different turn...

As soon as Elijah and William were next door to each other, the relationship between them worsened. Manor Farm was beside the canal, the back door facing towards Heave-Up Bridge. Elijah had to pass William’s house when he went from his farm along the path to Round Thorn Bridge, and as William owned this path, he occasionally ‘exercised his rights of ownership’. On one occasion William accused Elijah of stealing a dog, ferret and trap, and later for stealing fowl. William became increasingly unpopular in the village, such that he became known as Red Indian, and the locals, especially Elijah, frequently wound William up by singing this libellous song, the author of whom was never revealed, for hours on end:

There is a man, an Indian red, who all the people do him dread;

The cocks and hens begin to squeak when into the henroost he does sneak.

He married a wife of the Zulu race, who professes to be full of Gospel grace;

She goes to chapel and shouts Amen while Red Indian sneaks the ducks to his den.

The wind blew well, the buildings were dry; Says he, “Now I’ll my fortune try.”

To rob the insurance was his intent – so he struck a match and off it went.

When for money he did lack, something else went to rack,

So to satify his evil desire, he set his building all on fire.

In May 1887 Elijah and his wife were on the way to Whitchurch when they met a woman named Rebecca Millington. In conversation, Elijah reputedly threatened to shoot William. These threats continued until one evening in September, when Thomas Newbrook and Elijah were pulling potatoes about three quarters of a mile from the Pheasant Inn. Elijah told Thomas that he had bought a double barrelled gun to kill William. According to Thomas, Elijah called William “that enemy of mine”. Thomas insisted that Elijah was drunk at the time and would never have made such a threat had he been sober.

In October William met with PC Bowen and gave a statement against Elijah. Bowen went to interview Elijah but no further action was taken. A few days later PC Bowen saw William retrieving a double-barrelled gun from the hedge near the Waggoners’ Inn. PC Bowen warned him, “What are you messing about with that gun for at night? You are drunk in charge of a firearm. You will be shooting yourself or somebody else.”

About the same time in October, Elijah erected a gate from the public road at Round Thorn Bridge, at the entrance to the path which led past William’s house to his own house. William maliciously pulled the new gate up, perhaps in retaliation for hurdles of his own which Elijah had previously pulled up. The chain of events culminated in a conversation opposite Elijah’s farm, when William said, “I should like to knock you down,” and Elijah replied that William would get knocked down one of these nights and would not get up again in a hurry.

At about 6.30pm on 17th November 1887, a dark and frosty night, Elijah asked Thomas Craddock, who lived by Heave-Up bridge, to help him get his cows over the canal bridge to his fields. They could not get the cows over and Elijah had to take a longer way round which would necessitate him passing William’s house. Craddock watched him herding the cows off towards Round Thorn bridge, about 900 yards away. Craddock said that Elijah was in a good mood, not drunk at all. About an hour later William, his wife, his son Eli, and two daughters, Louisa and Rhoda, (their youngest daughter, Ada, must have been in bed), were sitting in their house when they heard singing outside. It was Elijah, singing the Red Indian song, and the sound of his singing seemed to be heading from his house, past Manor Farm, towards Round Thorn Bridge. William rushed out of the house, but was not carrying a gun. The singing continued for two or three minutes, but nothing else was heard by those within the house, until suddenly the singing stopped and two shots were fired. William’s wife screamed, her son Eli rushed out ahead of her carrying a candle, and found William lying on his back, almost dead, with a gun shot wound in his side. He was lying five yards from the canal near Round Thorn Bridge, 12 yards from the gate which was at the root of their latest arguments. William’s lips moved, but he did not speak, and he died within moments.

PC Bowen went to Elijah’s house and arrested him at about midnight that same night. He took him to his own house, in custody, walking past Manor Farm and Round Thorn Bridge to get there. Elijah admitted singing the Red Indian song whilst walking towards his home that night, rather than away, but denied knowing anything about the shooting. About 1am Superindendent John Edwards went to Manor Farm to examine the body, and then to Elijah’s house, where Elijah’s wife Betsy (Elizabeth Selina Forrester, nee Powell) let him in. Elijah’s gun was hanging over the mantelpiece and showed signs of being recently fired, although a witness later stated that Elijah had been out shooting the day before. The two policemen returned to Bowen’s house and charged Elijah with murder. Elijah continued to deny the crime. They took him to Whitchurch lock-up to await trial.

Thomas Newbrook failed to attend the first police court, claiming that was threatened by a local butcher with his life if he gave evidence against Elijah, who was well-liked. He claimed that many other people had threatened to have nothing to do with him if he spoke out against Elijah. On 9th March 1888 the case came to the Crown court. Mr Jelf defended Elijah, arguing that the gun might have gone off by accident during the course of a struggle. He called an expert in gunshot wounds, Dr John Gill of Welshpool. Dr Gill examined the evidence, and experimented with shots from two guns at various distances. He concluded that the shot was made at very close range, between 2 foot six and 2 foot 9 inches, and that William, not Elijah, was holding the gun when it discharged. A second expert witness, Dr Oliver Pemberton, agreed that the shot was fired at close range, pointing upwards, and that William was probably holding the muzzle of the gun when it was fired. The prosecution, however, rejected this evidence, since there were no further indications of a struggle.

After ten hours, the Jury left to consider their verdict. Elijah was calm at first, but the large assembly of onlookers in the courtroom were excited, speculating on the outcome. Elijah became increasingly anxious, but remained outwardly dignified and brave. After about twenty minutes the Jury returned. Elijah stood and faced the judge with his arms folded and head erect. As the moments passed before the verdict was given, he became more and more anxious, and looked as if he might give way. Finally, to his evident relief, he was pronounced guilty of manslaughter. The judge deferred sentencing to the following day. He was sentenced to 15 years penal servitude. His Lordship Mr Justice A L Smith said:

“Elijah Bowers Forrester, the Jury have found you guilty of having feloniously killed and slain your brother in law, William Powell.”

“My Lord, it was by accident!” interjected Elijah. The Judge continued:

“The Jury did what, in my opinion, they had a perfect right to do – to take a lenient view of your case. They have negatived the defence that was so ably put on your behalf, that death was caused by an accident; they have negatived also the charge that you have been guilty of wilful murder. and have found you guilty of having killed your brother in law absolutely without excuse. Now it is proven beyond all question that you harboured hatred and ill-will against the dead man, and in my judgement it is also proved that he harboured enmity, hatred, and ill-will against you. Upon this night of the 17th November, you, having considerately and consistently for some time been twittering him and annoying him by singing this song in the neighbourhood, go down to his house for the purpose of doing that, and you took with you this gun, a double-barrelled gun, loaded with powder and shot. For what purpose you took that gun, you know best, but with that gun you shot your brother in law, and took his life without lawful excuse. Now this, as you know, is a grave offence, and is next to that of wilful murder known to the law. Last night I made up my mind as to the sentence I was about to pass upon you, but in case I might have made a mistake of judgement I ordered you to stand down in order that I may consult superior counsel, and take superior advice. I have done so, and my own opinion has been confirmed and fortified, and I shall sentence you to Penal Servitude for 15 Years.”

There were expressions of surprise in the courtroom, and Elijah seemed greatly affected. He was first confined in Parkhurst, then by 1891 he was at the Convict Prison in Portland, Dorset, but it appears that he was still under the care of Parkhurst. In 1898 he was transferred from there to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, in Crowthorne, Berkshire. Elijah’s sentence ended in 1903, but his mental health was by now severely compromised. On 27th April 1909 he was committed to the County Lunatic Asylum in Cotford, Devon. He was discharged on the 31st March 1911, although it was said that his condition had not improved. He eventually returned to Shropshire. Sadly his wife Betsy died in 1919.

In 1939 Elijah was a patient in Salop Mental Hospital, in Bicton, Shrewsbury, and he was presumably still an inmate in 1944 when he died in Bicton. His address in his probate record is given as Rye Hills, Whixall. Shropshire Records and Research Centre hold admission and discharge documents for this period, so it might be revealing to search for records relating to Elijah.

The end of Thomas Newbrook’s story is a slightly happier one, but not without its own difficulties. I believe that in 1889, at the age of 51, he married Ann Calcott, who was fifteen years his junior. He had not mended his ways – he was fined ten shillings for drunkenness both before and after his marriage, in October 1888 and July 1891. Thomas and Ann had two daughters, Mary Ann, who was born in 1890, and Deborah, in 1893. Sadly Deborah died the following year. Thomas Newbrook died in the Whitchurch registration area in 1917.